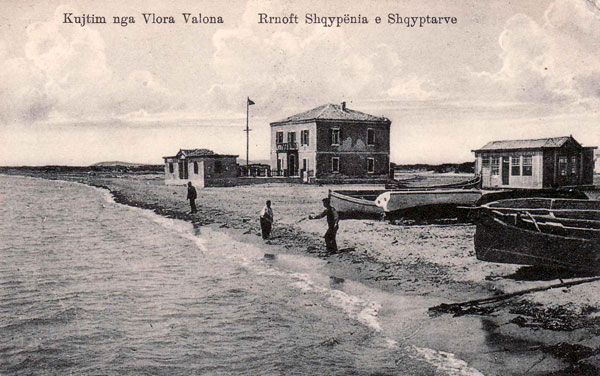

Site of Albanian Independence in Vlora

AlbanianHistory.Net by Robert Elsie

Lea Ypi e ka gjetur shumë interesant librin “Memuaret e Ismail Kemal Bej Vlorës, 1920” në anglisht. Nuk e di a gjendet i përkthyer në shqip apo jo. E habitshme do të ishte sikur ky libër i themeluesit të shtetit shqiptar të mos jetë përkthyer në shqip. Lea ishte habitur se Ismaili nuk kishte treguar interesin e duhur për shtetin shqiptar, por si t’i shërbente Perandorisë…

– Prandaj mund ta gjeni online në këtë adresë:

[ https://archive.org/details/memoirsofismailk00ismauoft/page/1/mode/2up ]

– Por edhe mund ta [ shkarkoni në PDF këtu, ] në 426 faqe. Në anglisht. Kurse këtu po sjellim prezantimin, që i bën Robert Elsie këtij libri.

1920

Ismail Kemal bey Vlora:

Memoirs

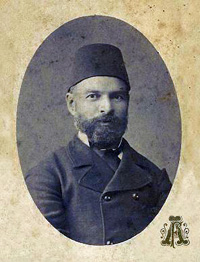

Ismail Kemal bey Vlora, 1884

Ismail Kemal bey Vlora, 1884

Political figure, Ismail Kemal bey Vlora (1844-1919), also known as Ismail Qemal bey Vlora, and in Albanian commonly as Ismail Qemali, was born in Vlora. He attended the Zosimeia secondary school in Janina and moved to Istanbul in May 1860. There he worked as a translator for the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs and subsequently for district administrations in Janina (1862-1864) and Bulgaria (1866-ca.1877), carrying on business activities at the same time. As a supporter of the assassinated Turkish reform politician Midhat Pasha, he was interned in Asia Minor from 1877 to early 1884, but then became governor of Bolu. In the following years, he was governor of Gallipoli (1890), governor of Beirut (1891) and a member of the council of state in the late 1890s. He left in the summer of 1900 for Italy, France, Belgium and England and only returned to the Ottoman Empire after the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, when he represented Berat as a member of the opposition in the Turkish parliament. In the spring of 1909, he took part in the counterrevolution against the Young Turks and founded the “Ahrar” (Liberal) party which sought to decentralize the empire. He hastened to Vienna at the outbreak of World War I to negotiate with the Austrian Foreign Ministry on the future of Albania. On 19 November 1912, he sailed to Durrës on an Austro-Hungarian naval vessel and travelled on to Vlora, where he headed the national assembly which declared Albanian independence on 28 November 1912. It was Ismail Kemal bey Vlora who read out the proclamation. He was forced to resign on 22 January 1914 and transferred government authority to the International Control Commission. He then went into exile to Italy, Barcelona and France, where he dictated his memoirs to the British journalist Sommerville Story in early 1917. He died of a stroke in Perugia in Italy. The memoirs of Ismail Kemal bey concentrate on his career as an Ottoman diplomat. The final chapter, however, contains the following account of the event for which he is best remembered.

In the last fifty years, this state of things has undergone a great change. In the first place, the death of Ali Pasha, and the noxious and incoherent policy of his successor, Mahmoud Nedim Pasha, and thereafter the political and territorial changes brought about in the Balkan Peninsula as a sequel to the Russo-Turkish war of 1877, were the first signals of troublous times for the Albanians. These last-named events showed them that they could not face the future for their country with the same sense of security as they had felt in the past. The Treaty of Berlin, which gave international sanction to the rights of the Balkan nationalities, added to the defence of these rights made by the British delegate, Lord E. Fitzmaurice, before the International Commission at Constantinople for the elaboration of the organic law of the vilayets of Turkey in Europe, were events that calmed the minds of the Albanians without absolutely reassuring them. The spectre of future dismemberment continued to torment them.

The fall of the Beaconsfield Cabinet and the naval demonstration undertaken on the personal initiative of Mr. Gladstone, with the object of assuring the immediate handing over to Montenegro of country torn from Albania, shook their confidence in Great Britain. My countrymen, who had always reposed their faith in the desire for impartiality and equity entertained by the Liberal Governments, especially that of Great Britain, were more concerned at the fear of being abandoned by this latter Power than by the amputation their country had sustained for the first time since its incorporation in the Ottoman Empire. Happily this apprehension did not last long. Mr. Goschen, who had been sent to Constantinople as Ambassador Extraordinary, undertook, as I have said above, to defend the rights and interests of the Albanian people. The verbal assurances he gave to our compatriot, Abeddin Pasha, Minister for Foreign Affairs at that time, and his official reports to Downing Street, were of a nature calculated to reassure the most sceptical of Albanians as to the British Government’s real political views and their desire to see justice done to our people.

Unfortunately the Porte, whose interest it was to bring about the unity of the Albanian territories and to fortify the ethnical element, was the first to adopt the opinion of those who had an interest in seeing the country disunited and enfeebled. Thenceforward the Albanians began to see clearly and to take into account the new situation created in the Balkans, and the danger menacing their national existence. From this period, too, irrespective of their region or religion, they manifested more clearly their conviction of racial individuality, as distinct from that of the other peoples of the Balkans, and affirmed more and more their decision not to be subjugated by any foreign Government, Greek or Slav.

Abd-ul-Hamid, whose chief preoccupation was always his own personal safety, had appreciated the faithful character of the Albanians from his youth up, and did his utmost, in his usual way, to obtain personal benefit from the fact. The person of the Sultan, his palace, and even his harem, were entrusted to Albanians. In the Ministries and in the civil and military services, Albanians occupied the highest and most distinguished positions. Despite these favours, my countrymen never renounced their national sentiments or their legitimate aspirations, although they religiously observed the oath of fidelity to the Ottoman dynasty which their ancestors had taken. During this reign of thirty odd years they never let slip an opportunity of showing their desire to be what they had been before their submission to the Turk. The smallest political event in the East found an echo in Albania, when the people of the country would meet either in a populous centre or in some distant and inaccessible mountain pass to discuss matters, and thereafter present their claims to the Sovereign himself. It must be confessed that Abd-ul-Hamid followed every Albanian movement very closely, and, whether from personal or political reasons, never failed to pay the most serious attention to the demands and susceptibilities of these subjects.

The last phase of Macedonian affairs, and the decision taken by Europe regarding the organisation of this country, seemed to the Albanians likely to compromise their national unity. They began in consequence to feel acute anxiety, wondering what fate was in store for their country. It was at this critical juncture that the Young Turks asked for their aid in the execution of their political programme—which at the first blush seemed to conform with Albanian national aspirations—of uniting all the various ethnical elements under the same flag of justice and equality, and thus checkmating foreign envy.

Ten thousand armed Albanians met at Ferizovic on July I5th, 1908, and sent to the Sultan a famous telegram, which produced a greater impression upon him than the remonstrances of all the Turks or all the diplomatic representations of Europe.

The telegram sent to Muhijeddin Bey, Turkish Chargé d’Affaires in Paris, on July 22nd, asking him to “confer with Ismail Kemal Bey,” and get an immediate reply, was referred to in a previous chapter.

My reply advised His Majesty without a moment’s delay to promulgate the Constitution, which was the only efficacious remedy and the only sure way of grouping round his throne all the peoples of the Empire. And, as I understood the morality and mentality of the Young Turks, as well as their motive for the political course they were pursuing, I also recommended His Majesty to take all necessary measures to prevent aggression on the part of the adventurers in power, and to attract to himself without their intervention the confidence and help of the Albanian population. Two days later the Constitution was promulgated; and in obedience to a fresh order of the Sultan, a report setting forth my plan, which I had laid before the Chargé d’Affaires, was forwarded to the Sovereign by the same channel.

The Albanians soon discovered the real intentions of the Committee of Union and Public Safety, and perceived the gulf that lay between their own political conceptions and the Unionist programme. By union the Albanians understood a grouping of different races under the flag of the Ottoman Constitution, which would strengthen the Empire by the union of all its peoples, guaranteeing to each its national existence. The Committee, on the other hand, only thought of uniting all the different races by forcing them to deny their origin; and, in proportion as their position in the Government was confirmed, so their ambition to carry out this programme increased. The first consequence of their course of action was the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary and the proclamation of Bulgarian independence.

During my stay at Valona, my native town, I learned from a reliable source what the directing idea of the Committee was, and how the central committee of Salonica had contrived to bring about this political change. Their object was to ensure the triple advantage of (i) obtaining popularity for themselves throughout the country; (2) discrediting the former statesmen, of whom they wanted to get rid at all costs; (3) using this political liquidation as a means of ridding the country of foreign influence, so as to be able to apply their policy of racial unification with the utmost vigour. On my return to Constantinople I hastened to put Kiamil Pasha au courant of what was going on, and urged him no longer to tolerate the working of the revolutionary committees, the existence of which constituted an anomaly and a grave danger for the establishment of a regular government. Unfortunately the old Grand Vizier committed the blunder of trying to use this as a bogey to frighten the Sultan.

The Committee, growing bolder, and without waiting for the termination of the negotiations with Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria, seized power by a coup de main. The first act of the first Unionist Cabinet was the promulgation of the famous draconian law on the Bands, the sole object of which was to legitimise a criminal attempt on Albania. The Young Turks, who saw in the Albanians merely a Mussulman people having no political ideal beyond a desire to avoid the payment of taxes, were convinced that by management and the exertion of pressure they would become docile and common Ottomans, and would serve as an example for the other nationalities. Nursing this hope, they made, in a space of less than two years, four expeditions against Albania. But the Albanians, who had in the course of centuries past resisted the power of so many Empires, and who had not been lulled to sleep even in the time of Abd-ul-Hamid, were not terrified by these efforts. On the contrary, the aggressive policy of the Young Turks was the leaven that caused their national sentiments to revive and flourish afresh. The successes which the armies of Djavid and Chevket obtained here and there over the Albanians only stirred to flame the embers of revolt.

The Albanians, however, whose enthusiasm never carries them beyond their natural character, gave, even at this critical moment, proofs of political moderation and foresight. While their blood was flowing copiously for the defence of their national rights, I in my capacity as leader, with my Albanian colleagues, made every possible effort, both in the public sittings of Parliament and at private meetings with Ministers, to bring the Turkish Government and Chamber back to reason and to a sense of patriotic duty by showing the true sentiments which animated the Albanians in general towards the Sultan and his Empire, and pointing out the danger of a senseless struggle. But all our sincere warnings remained unheeded.

In the summer of 1911 I went to Cettinje to join the chiefs of the Malissori, who had taken refuge with their families in Montenegro before the threats of Chekvet Tourgout Pasha. I ought here to express our gratitude to King Nicolas, who aided me in my task by his friendly welcome, and helped the families who had taken refuge in Montenegro with kindliness and humanity. After a brave resistance, all the delegates of the Malissori signed, at a meeting at Gertché, a memorial drawn up at my instigation, which contained the twelve points of the national claims, renewing once more at the same time their assurances of attachment to the Ottoman Empire. Unfortunately, this period of appeasement was but short-lived. The new Chamber, whose election had been imposed with a view to strengthening the position of the purely Young Turk Government, recommenced the game of taking back with one hand what they had given the previous day with the other.

Troubled by this fresh attitude of the Porte, and being convinced that the war with Italy would lead to a general war in the Balkans, enveloping Albania from all sides, I addressed a circular from Nice, whither I had retired, to all the Albanian centres, reminding them of the imperative necessity of being ready to face any eventuality. These gloomy previsions, and the general discontent caused by the Tripolitan war, forced Albania to a general rising. The savage obstinacy of the Young Turks in their attempt to absorb the nationalities had made our resistance inevitable and compelled us to fight for our national life. Challenged and attacked as we were in our existence as a people, though we felt how much this struggle would be contrary to our unabated desire to stand by the Empire, had we not above all things a right to work out our own salvation? The general rising and the triumphal entry of the chiefs of all the tribes into Uskub put an end to the extravagant and criminal power of the Young Turks and brought about the dissolution of the Chamber. Our patriotic aims were attained, and from this time onward we returned to our allegiance to the Empire.

Leaving Valona again for Constantinople, I was visited, on my arrival at Trieste, by Colonel Beckir, who told me that Prince Mirko of Montenegro wanted to have a conversation with me at Porto-Roso, near Trieste. When I saw him, the Prince showed me a telegram from the King, his father, inviting me to meet him at Antivari, and discuss the part that Albania could play in the war against Turkey and the advantages she was likely to derive from such participation. This interview, however, did not take place. I considered it to be premature, and thought it better, in every respect, as I explained in my telegraphic reply to King Nicolas, that I should first approach the new Cabinet, the principal Ministers in which were personal friends of mine, in order to try to arrive at an understanding. But, when I made these advances, I found I was simply butting against a blind obstinacy that refused to recognise the gravity of the situation, or to consider the menaces that I left them to guess at, without betraying the confidences which I had received at Porto-Roso. The Porte considered that palliative measures would meet the case, and refused to take the energetic steps required. And as, in view of this attitude, the Balkan Allies had declared war on Turkey, and the Bulgarian armies were in occupation of Kirk-Kilissé, while the Serbs had seized Uskub, I realised that the time had arrived for us Albanians to take vigorous measures for our own salvation.

The Grand Vizier, Kiamil Pasha, pressed me to stand by him, and offered me a portfolio in his Ministry. In other circumstances I should have accepted this post of honour with pleasure, but now a higher duty forced me to decline it. My place was no longer there, and I owed my services entirely to my own country. Kiamil Pasha finally bowed to reasonings the urgency of which he could not but recognise, and we separated with mutual regrets. On my return journey I arrived at Bucharest, where there was a large Albanian colony. As the result of a meeting we held there, fifteen of my compatriots decided to go back with me to Albania. I telegraphed to all parts of Albania to announce my arrival, and declared that the moment had come for us to realise our national aspirations. At the same time I asked that delegates should be sent from all parts of the country to Valona, where a national congress was to be held.

At Vienna I received a telegram from a personal friend at Budapest, who invited me to go thither in order to have an interview with a highly-placed personage. My first visit at Budapest was to Count Andrassy, where I met Count Hadik, his old friend and former Under-Secretary of State, who told me that the person I was to see was none other than Count Berchtold. I met the latter the same evening at Count Hadik’s house. His Excellency approved my views on the national question, and readily granted the sole request which I made him, namely, to place at my disposal a vessel which would enable me to reach the first Albanian port before the arrival of theSerbian Army.

As Valona was blockaded by the Greek fleet, I was glad to disembark at Durazzo. There we found awaiting us two Greek warships, which had been there since the previous evening. Our captain was very anxious about us, not without cause; and we shared his concern. But the officer who came on board, after making a scrupulous examination, in the course of which he found nothing but a few arms in the possession of my companions, left me free to land, and our vessel continued her journey.

We found the people of Durazzo in total ignorance of all the events that had been taking place. Deceived by the sparse news which reached them through prejudiced channels, they believed that the Turkish Army was victorious, that it was in occupation of Philippopolis, and was marching on Sofia and Belgrade. They did not even know that the Serbs were at their very gates. Our arrival occasioned some excitement in the town, which was fomented by the Turkish element, joined by a portion of the local population, consisting mostly of Bosnian immigrants, who spread the report that we were agents provocateurs. This special and local feeling had not prevented Durazzo and the dependent districts from appointing their delegates to the national congress, and these left for Valona with me and my little band of Albanians from Bucharest.

We travelled on horseback, and, before arriving at our first stopping-place, I learned through a notable of the neighbourhood, who came to meet me, that orders had been telegraphed by the Turkish Commander-in-Chief at Janina to the local gendarmerie to arrest me and take me to his headquarters. We accordingly changed our route, and passed the night in another village. The next morning the chief of gendarmes who was to have carried out this arrest brought me a telegram from the same Commandant at Janina, which asked the local authorities to receive us with honour and do what they could to help us on our journey. This, however, far from calming our fears, rather confirmed the alarming news I had heard the previous evening; and so, avoiding the route on which we were being watched, I took a safer one, and we finally arrived at Valona. Here our reception was quite different from what it had been at Durazzo. A holy fire of patriotism had taken possession of my native town, and public enthusiasm and delight greeted us everywhere. In a short space of time I found myself surrounded by eighty-three delegates, Mussulmans and Christians, who had come from all parts of Albania, whether or not they were occupied by the belligerent armies.

The Congress was at once opened. At its first sitting—November 15th-28th, 1912—it voted unanimously the proclamation of independence. The sitting was then suspended, and the members left the hall to hoist upon my house—the house where I was born and where my ancestors had lived—amid the acclamations of thousands of people, the glorious flag of Scanderbeg, who had slept wrapped in its folds for the last 445 years. It was an unforgettable moment for me, and my hands shook with hope and pride as I fixed to the balcony of the old dwelling the standard of the last national Sovereign of Albania. It seemed as if the spirit of the immortal hero passed at that moment like a sacred fire over the heads of the people.

On the resumption of the sitting, I was elected President of the Provisional Government, with a mandate to form a Cabinet. But I considered it proper that the Ministers should also be elected by the Congress, and so I waived this prerogative, only reserving to myself the distribution of the portfolios. The Government having been constituted, the Congress elected eighteen members who were to form the Senate. I notified the constitution of the new State to the Powers and the Sublime Porte in the following telegram:

“The National Assembly, consisting of delegates from all parts of Albania, without distinction of religion, who have to-day met in the town of Valona, have proclaimed the political independence of Albania and constituted a Provisional Government entrusted with the task of defending the rights of the Albanian people, menaced with extermination by the Serbian Armies, and of freeing the national soil invaded by foreign forces. In bringing these facts to the knowledge of Your Excellency, I have the honour to ask the Government of His Britannic Majesty to recognise this change in the political life of the Albanian nation.”

“The Albanians, who have entered into the family of the peoples of Eastern Europe, of whom they flatter themselves that they are the eldest, are pursuing one only aim, to live in peace with all the Balkan States and become an element of equilibrium. They are convinced that the Government of His Majesty, as well as the whole civilised world, will accord them a benevolent welcome by protecting them against all attacks on their national existence and against any dismemberment of their territory.”

I had but one dominant thought, now that I was given presidential power, and that was to organise the small extent of country that remained to us, and to show the Great Powers that Albania was capable of governing herself and deserved the confidence of Europe. As to the future Sovereign, the interest for the moment did not lie so much in the choice of his personality as in the principle which was to decide the choice between a European and a Mussulman prince. My own views frankly favoured a Christian and European, and in this I was supported by all the Albanians as well as by the political considerations that had to be taken into account. Only a European Sovereign could properly guide us in the great European family we were entering. The question of religion did not enter into consideration in this preference for a European, since all the three cults practised in the country—Mussulman, Catholic, and Orthodox—had equal and complete liberty, no rivalry or pre-eminence being possible.

The Sublime Porte, immediately on receiving our notification of independence, set itself in opposition to our aspirations. The Grand Vizier, in a telegram replying to my note, tried to impose on us, as Sovereign, a member of the Imperial family. According to him, Albania could only be saved by being the vassal of the Ottoman Empire, with a Prince of the Imperial family. On what Power, he asked, did she expect to rely? On Austria? On Italy? Let her not forget, he added, the example of the Crimea, for which independence under the protection of Russia was but the prelude to complete subjection. My reply was that Albania relied neither on Italy nor Austria, but on the rights of the Albanians to exist and have a nationality of their own, as well as on the duty of the Powers to respect nationalities. I added that Turkey could not but be a bad advocate of the cause of free nationalities, and that Albania would prefer to defend her cause herself, but that, on the other hand, when the final solution came, she would do all she could to prevent the new situation from being an obstacle to good relations with the Sublime Porte. So ended what I may call the first candidature to the Albanian throne, which was followed by others that had no weight at all with the Albanians, who placed their confidence in the Great Powers.

In spite of this attitude of the Porte, and of the menace of the Turkish Armies, which still occupied a portion of the country, we spent our time in organising the administration and maintaining order in the portions left to us. The silence of the Great Powers and their indifference in face of Serbia’s invasion and devastation of our land, at the same time that Greece was blockading and bombarding the town of Valona and the littoral, disgusted us. A little later, the Greek fleet having cut the cable which was the only channel of communication with the outer world, we were completely isolated and deprived of all knowledge of what was taking place beyond our borders.

One evening, towards the end of March, 1913, we learned that a vessel flying the British flag had anchored in the port and announced that the blockade was suspended. We were naturally delighted with the news. Next morning I learned that this vessel was the yacht of the Duc de Montpensier (younger brother of the Duc d’Orléans), and a little later a messenger came to me from the Duke carrying a letter in which His Highness informed me of the object of his visit, namely, his desire to become a candidate for the throne of Albania. There followed an invitation to lunch on board the yacht. I accepted, and after luncheon the Prince and I had a long conversation. He confided to me his intentions very frankly. I assured him I was happy and flattered, both for myself and on behalf of my country, that a Prince of the French Royal house should aspire to the difficult but honourable task of reigning over Albania. But I was forced to add that, as the blockade had kept us in total ignorance of what was our exact situation with regard to the European Powers, we regretted we were not able to take the decision, even if it were one in conformity with our wishes.

Next day His Highness came to pay us a visit at Valona. He made a tour of the town, in which he was able to notice the excellent impression he himself made—a sympathy which later caused all the more regret to the people and myself. I left with the Prince on his yacht on April 1st, 1913, for the purpose of conferring with the Powers. He left me at Brindisi, and continued his voyage to Venice. I went successively to Rome, Vienna, Paris, and London. No understanding had been come to and no decision taken on the question of this candidature, which would have been so welcome to the Albanians; and there the matter ended.

My object in making this journey was to fight the cause of the territorial integrity of Albania with the Powers, but especially in London, where the Conference was deliberating on the settlement of the Balkan question. I also wanted to hurry on the selection of the future Sovereign, which would help to ensure the stability of the national Government and remove all internal difficulties which the continuance of provisional conditions necessarily engendered.

In Vienna Count Berchtold, in our first interview, allowed me to perceive how slight was the hope that Albania would be permitted to preserve her territorial integrity, in spite of her rights and in spite of the efforts he had himself made. It was the first painful blow to me, but worse was to come, for on the day when I left Paris for London came the news of the surrender of the town of Scutari by Essad Pasha to the Montenegrins. This disaster, which took place while the fleet of the six Great Powers was manoeuvring before this port in order to force King Nicolas to raise the siege, jeopardised the integrity and almost even the existence of Albania. The question of the candidature to the throne was by this fact necessarily relegated to a secondary place, and all my efforts had to be devoted to the territorial question.

On my arrival in London the same evening, I was happy to find myself again in the sympathetic atmosphere to which I was accustomed there, and I gathered renewed strength for my political struggle for the rights of the peoples of the East. The sincere sympathy shown by the British press and people towards our national cause, and the kindly welcome extended to me by Ministers and Statesmen of this great country, led me to hope that our indisputable rights, which were in no way incompatible with the political interests of Europe in general, or of our neighbours in particular, would be acknowledged by the Conference. Never was a nobler task offered to the Great Powers; never was a solution so necessary; and never had we had such hopes of obtaining it as at this moment, when the Powers were for the first time called on to form a Congress, whose task was not only to conciliate opposed interests, but also to act as an international High Court of Justice.

Of all the Balkan questions treated at this Conference, in my view the foremost, the most interesting, and, above all, the most eminently European, was that of Albania. We thought it possible to hope that a people so worthy of interest by reason of its antiquity, its valour, and the services it had rendered to Europe, first by defending it against the invasion of the Turks, and then by resigning itself to a docile submission when it had become the pivot of European equilibrium, might have been allowed to become master in its own house and to retain its national independence. The Albanians, delivered from the Turkish yoke, of which they had for centuries been less the instruments than the victims, would have been happy to recover their liberty and independence, and therewith the repose of which they stood in such great need. They had no other claims to make, no other pretensions to put forward. They desired that the work of restoration should take place for all the Balkan peoples as for themselves, that hatred and envy should cease, that all legitimate rights should become sacred, and every unjust ambition or enterprise meet with its condemnation in a guarantee of solidarity on the part of the Great Powers. Sure of the justice of our claims, we awaited with entire confidence the verdict of the Conference of the Powers.

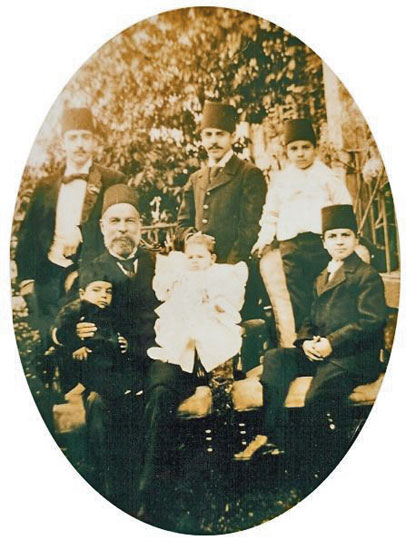

Ismail Kemal bey Vlora and family, 1896

But the sympathy shown to me in my mission was the only consolation offered to Albania’s broken heart when we learned the decision which the Conference of London had taken. More than half my country’s territory had been attributed to Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece. The most nourishing towns and the most productive parts of the country having been taken away, Albania was reduced almost to its most arid and rocky portions. Thus plunged again into deep depression at seeing the future of our reborn country so darkened, we were comforted by being told that we had had to be sacrificed to the general interests of Europe. Resigned, but not despairing, I returned to Albania buoyed up by the single hope that more favourable conditions would at some future time permit Albania to realise her legitimate desires.

On my return to Valona in June 1913, the Provisional Government redoubled its efforts to organise the country and maintain order. It was a task which might well have seemed impossible, but was facilitated by the Albanian character, whose patience, foresight, and unflinching patriotism in the midst of all these complications and anxieties cannot be too highly praised. It was thanks to the virtues of this race in a country of which the frontiers were still undetermined, where the political statutes promised by Europe were awaiting their fulfilment, and where a frantic propaganda was carried on with the object of provoking trouble—it was thanks to these virtues that my Government succeeded in bringing stability to the State and assuring it a normal administration.

But despite the satisfactory results in the present, the future was dark and uncertain so long as the question of the future Sovereign remained unsettled. I therefore addressed a pressing appeal to the Powers in the following terms:

“If the Provisional Government of Albania, which has for eleven months been struggling with innumerable difficulties, has been able to maintain order and relative tranquillity in a country harassed on all sides by enemies who have sworn its destruction, it does not claim for itself the merit, which in fact is due only to the patriotism and the resignation of the Albanian people.”

“But this provisional state of affairs cannot be continued indefinitely without encountering insurmountable difficulties. We believe we have reached the extreme limit of the people’s patience, and we hasten to submit to the consideration of your Government the unanimous wish of the people and the Government for the designation and enthronement of the Sovereign, whose mere presence will suffice to unite all classes of the population in the work of consolidating Albania and organising her administration.”

“In the hope that the guaranteeing Powers will take our request into serious consideration, the Provisional Government would be ready to take any steps necessary to hasten the happy result which Albanians await with such impatience.”

It was a short while after this telegram had been sent that the name of the Prince of Wied was first mentioned in connection with Albania, vague rumours concerning his candidature being spread about. These rumours soon became more definite, in a way that recalled a curious campaign started on behalf of Prince Ahmed-Fuad, of Egypt, by the Zeit of Vienna; in this case the propaganda was launched in the form of a highly dithyrambic article in the Oesterreichische Rundschau (also published at Vienna) over the famous pseudonym of the Queen of Roumania. “Carmen Sylva,” more poetess than ever, after having evoked Albania vainly clamouring for a Sovereign, in the style of a recitative of the “Nibelungen-ring,” proposed to her as guide the scion of an ancient race dwelling on the Rhine. She then gave the genealogy of the Prince of Wied, and his history since his childhood. The prospect of confiding the destinies of Albania to this unknown celebrity did not particularly enchant me, but what troubled me more was the propaganda that began openly in favour of this candidature, in which money and presents were distributed with cynical effrontery. I asked for official information as to this candidature, and, being informed that it was not under consideration, I no longer hesitated to take rigorous measures against the propaganda or to expel the agitators. But, though the reply to my question was so emphatically in the negative, destiny had doubtless willed otherwise, since I was officially notified a little later that the six Powers had come to an unanimous decision regarding the choice of Prince William of Wied, and that nothing remained except to ratify it by the formality of a popular election. The Albanian people, unshakenly confident in the decisions of Europe, sent their votes at once to the Provisional Government, which communicated the result to the Powers.

Coloured postcard of Prince Wilhelm zu Wied, 1914

Coloured postcard of Prince Wilhelm zu Wied, 1914

However, though all was arranged, the Prince of Wied gave no sign, at any rate in the direction of Albania. We expected him to arrive every day. His departure was announced, but he did not arrive. These inexplicable delays were utilised by the Young Turks, who recommenced with even greater energy than before their campaign in favour of a Turkish Prince. I then appealed to the Commission of Control, begging them to draw the attention of the Powers to the urgent need for the enthronement of the new Sovereign. In case particular reasons were delaying the arrival of the Prince, I asked that a Commissioner should take over the Government in his name, or that the Powers should instruct the Commission itself to assume authority on their behalf. In my opinion some such arrangement was the only way of straightening out the internal difficulties and terminating the intrigues which tended to cause disorder in the country. My request was at last approved by the Powers, and the delegates came to notify me that they were authorised by their respective Governments to assume the power if I maintained my view on the advisability of this step. The following protocol was signed on the spot:

“This 22nd of January, 1914, the International Commission of Control has met in the presence of His Excellency Ismail Kemal Bey. The President of the Provisional Government, being persuaded that the only means of terminating the condition of disruption and anarchy ruling in the country is to constitute a single Government for the whole of Albania, and that in the present circumstances this end can only be attained if he places the power in the hands of the International Commission of Control representing the Great Powers, has repeated the request that he has already made to the International Commission of Control, in the presence of the Ministers, to take over this task and accept the placing of the power in their hands. The International Commission of Control pays homage to the patriotic sentiments which have dictated the actions of His Excellency Ismail Kemal Bey, accepts this delegation of power, and, duly authorised by the Great Powers, assumes the administration of Albania in the name of the Government it represents.

Valona, January 22nd, 1914.

Signed : “Ismail Kemal, Nadolny, Petrović, Krajewski, Harry Lamb, Léoni, Petriaew.”

As soon as I had handed over the power to the Commission, I left for Nice in order to take a well-earned rest. I naturally followed from this distance with intense interest the march of events in my own country. It was not long before I learned—and I did so with great pleasure—that the Prince of Wied had at last made his solemn entry into Durazzo. I was, however, extremely annoyed that he had chosen for his capital one of the towns which was the least appropriate for the Royal residence, and the numerous disadvantages of which I had already pointed out, disadvantages which had been understood and recognised by the Foreign Office in London. But for the moment this dark spot disappeared again from the horizon, and I did my best, in the bottom of my old Albanian heart, to look forward with hope to the new era. After long and cruel years of waiting, after so many alternations between hope and disappointment, I tried to forget my own impressions, and suppressed any latent disposition towards anxiety, thinking only of the thrilling spectacle of our first king setting foot upon the sacred soil of my Fatherland, and of the imposing fleet which the six Great Powers gave him as an escort. My gratitude went out to Europe, which had confirmed Albania in her national existence by thus giving her a Sovereign that she had herself chosen.

It was only later that I learned the details of this memorable day. The Prince of Wied was accompanied by the Princess, his wife, and their children. His Court consisted of a marshal and a doctor (both Germans), a private secretary (an Englishman), and two Ladies of Honour. His bodyguard, which one might have expected to find of some importance, consisted of a couple of rather ferocious dogs. On board the vessel which brought him the Prince had the 10,000,000 francs which Austria and Italy had advanced him in anticipation of the 75,000,000 which the other Powers had not yet decided to pay. He was received with enthusiastic acclamations by the population, while salvos of welcome were fired in the port. His first act, even before disembarking, was the nomination of Essad Pasha as Minister of War and first general of Albania, and Essad accompanied the new Sovereign on shore.

William of Wied’s short reign, which was richer in grotesque episodes than in incidents tending to the reorganisation of a renascent State, displayed the little care that the Powers had taken in the choice of this Sovereign for a country whose happiness depended on a fortunate selection. We had hoped that the tact and wisdom of the Prince might have balanced the losses in territory that we had sustained, and that his advent might give a great impulse to the prosperity of the country. Instead of that, the situation became more and more complicated, and in a short while grew actually critical. One morning I received a short telegram from Valona which gave me cause for absolute consternation. The house of Essad Pasha had been bombarded and the Minister himself thrown into prison. This brief intelligence, without further explanation, seemed to me so extravagant that for the moment I refused to believe it. I hurried to the Austrian and Italian Consuls at Nice, and got them to telegraph urgent messages for me to Rome and Vienna in order to get confirmation of this news, if true, and to discover its meaning. The reply I received left no further room for doubt. A little later I learned the details of the affair from other sources.

I had always foreseen that Essad Pasha would find himself in an extremely awkward position at Durazzo. This town, of less than 5,000 inhabitants, had been the centre of the intrigues and hostility against the candidature of Wied as a European Prince, as well as of the revolt of Essad against the Provisional Government. Essad, who had suddenly, by means of a suspicious volte-face, been promoted Minister of this same Prince who was so undesirable to his compatriots, could only meet with unpopularity and contempt. The feeling against him grew rapidly more bitter. The popular demonstrations throughout the country assumed a threatening character; but, instead of trying to calm the people, when this agitation was at its height, the Prince met them with cannon. Instead of dismissing his unpopular Minister in a regular and legitimate manner, the Prince, acting under some influence which I am unable to fathom, again had recourse to violent measures and adopted a line of action unprecedented in the annals of government. Essad’s house being blockaded and bombarded, his wife appeared at a window shaking a sheet as a flag of truce. The bombardment ceased, the Italian Minister intervened, and, thanks to him, Essad Pasha was able to leave without incurring further danger. Guarded by sailors, the family left and were put on board the Austrian guardship, from which they were transferred to the Italian stationnaire, on which Essad sailed for Europe after giving his word of honour not to return to Albania.

In view of these extraordinary happenings I considered it my duty to return at once to Valona. Just as I was going to take the train at Nice, the Italian Consul came to me with a telegram from the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, San Giuliano, in which he asked for my opinion on Albanian affairs and on the measures that ought now to be adopted, as the situation was becoming more and more alarming. He asked me to discuss the matter with him, and accordingly I went to Rome, where San Giuliano and I came to an understanding as to the measures to be adopted.

At Valona, where, as soon as I arrived, I learned the details of what had taken place, I also found out that Durazzo was surrounded on all sides and no communications were taking place between it and the rest of the country. The supreme authority and jurisdiction of our Mbret was thus confined to this small and insignificant town. A few days later I left for Durazzo with fifteen notables of the district, in order to submit our views on the situation, which were in agreement with those of San Giuliano, to the Prince. In a tête-à-tête interview which I had with him, I told him the conclusion we had come to and the measures we deemed necessary. The Prince impressed me as having no proper idea of the state of affairs, and as being oblivious of the exceptional gravity of the moment. He seemed incapable of making an observation or putting a question arising from his own personal thought. While I was explaining the different ways that might be adopted to get him out of his difficulties, he never once asked me how I thought of putting them into practice.

The next day the Prince received the fifteen notables from Valona. He did not let us leave, however, without giving some sign of his solicitude for the country. A meeting of all the Albanian chiefs then in Durazzo was called at the Palace. The Prince opened it himself with a few words in French, explaining why he had summoned us, and inviting us to give our opinions personally on the situation of the country. We had had no preliminary discussion, as is usual when one is called upon to give opinions in such circumstances, but we did as he wished, I myself speaking first instead of concluding the series of speeches, as I ought to have done in view of my position.

The Prince thanked us, and said that, when he had had our remarks translated and had studied them, he would inform us of his decision. We waited for several days, but, as no further communication reached us, we returned to Valona.

In view of the aggravation of the general situation of the country and the evident incapacity of the Government at Durazzo, a public meeting of the inhabitants of the town and district, as well as of refugees from other parts of the country in the hands of the enemy, was held in the Grande Place of Valona, with a view to taking measures to save the country. After a long discussion it was decided to form a Committee of Public Safety, under my presidency. We informed the Powers and the Prince of this decision, in an address which stated that representatives of Valona and a dozen other places had met and voted the formation of a Committee of Public Safety with the object of asking the guarantor Powers and the Prince to transfer the Government provisionally to the International Commission of Control, as representing the Great Powers, and to take all measures that the circumstances demanded. The message, signed by thirty delegates, appealed to the justice of the Powers, and begged them to entrust the Commission with this task without delay, adding that it was “the only measure in our opinion that can keep the legitimate Sovereign on the throne, ensure national unity and territorial integrity, and save from destruction more than 100,000 human beings who, fleeing from fire and sword, had left their burnt and devastated homes and taken refuge in the only corner of Albania which remained free, the town of Valona and its neighbourhood.”

I have reached the last moments of this painful and futile reign. Shut up, as I have said, in his unlucky capital, the Prince had lost all authority, and his sovereignty was non-existent. There remained none of the ten millions that had been advanced to him and which he had stupidly wasted on such things as the creation of a Cour de Cassation (High Court of Appeal) when there were not even Courts of Law; the appointment of inspectors of public education in a country where there were no schools; and the maintenance of Ministers appointed to foreign countries who calmly remained at home. Though he sent his Minister of Finance to Rome to obtain fresh subsidies, both Rome and Vienna turned a deaf ear. Like a speculator whose business has failed, William of Wied realised that there was nothing left for him to do but to depart. The Great War had begun, and was soon to cover the whole of Europe. The fleets of the Powers left Durazzo to the mercy of chance, and the Prince followed them on a small Italian yacht that had been left at his disposal. In spite of their experiences in these three months, my countrymen watched him depart with sadness, as if he were a hope that was perishing, a dream fading away. He had done nothing towards trying to understand them. He had not made a step to reach their hearts, which had been so confidingly opened to him.

It only remains for us now to await the day when the representatives of civilisation and humanity will unite and decide on recognising our rights, which have so far unhappily been disregarded on the sole plea of trying to avoid that which was inevitable. We are convinced that a measure of justice accorded to us will be of advantage not merely for ourselves, but also for those who sought for their own aggrandisement in our destruction. The reconstitution of the Balkanic bloc and the guarantee of its independence will be one of the most efficacious factors for the peace of the East and of the world. This Balkan edifice can only be consolidated with and by the consolidation of Albania, which forms its fourth supporting column.

[excerpt from: Sommerville Story (ed.): The Memoirs of Ismail Kemal Bey (London: Constable, 1920), p. 363-386.]